Lost in Translation, Found in the Basement: Prototype Chinese Typewriter Unearthed

A routine basement cleanout uncovered a one-of-a-kind typewriter—and a forgotten milestone in language technology.

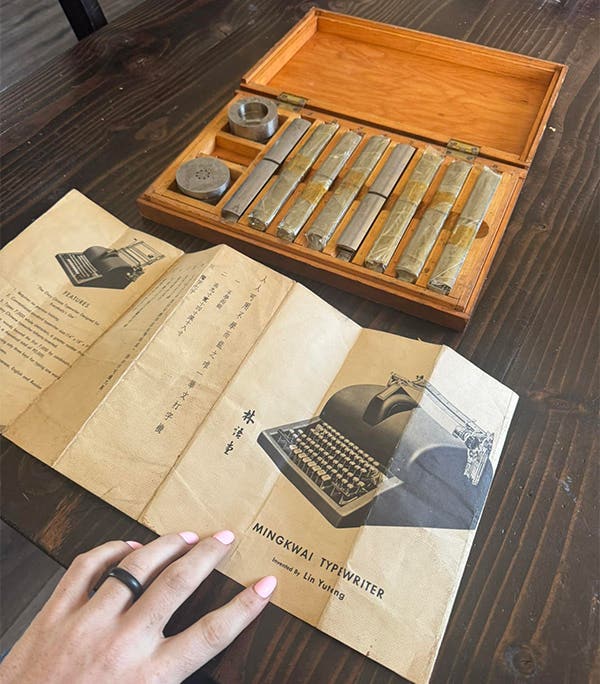

It started with a situation familiar to many readers: Earlier this year, Jennifer Felix was clearing out her late grandfather’s basement in New York. She and her husband found a typewriter among his belongings—again, not unexpected. But this typewriter was special: Instead of letters, the keys were labeled with Chinese characters.

A little research indicated that the typewriter was a machine called the MingKwai, but not much more than that. Felix and her husband posted pictures and inquiries online, including to the Facebook group “What’s My Typewriter Worth?” where they asked, “Is it even worth anything? It weighs a ton!”

Responses came rolling in. Many of them were expressions of surprise and delight from typewriter collectors, scholars, and museum curators. Some offered to buy the typewriter. The MingKwai typewriter wasn’t just one of a kind. It was a long-lost prototype of a legendary machine.

Chinese scholar Lin Yutang (1895-1976) invented the MingKwai (meaning “clear and fast”) in the 1940s. Lin was born in South China, studied at Harvard as a graduate student, and completed a PhD in linguistics at Leipzig University in Germany. Throughout his career, he wrote extensively in English and Chinese and translated numerous Chinese texts into English.

The Chinese Writing System

The Chinese writing system is not based on an alphabet but on characters that represent complete words, ideas, or grammatical particles. This kind of writing system has advantages, like allowing for communication between mutually unintelligible dialects (words with the same meaning can have radically different pronunciations but will be written as the same character), but is not well suited to keyboards. Lin came up with a 72-key typewriter and a mechanism that displays multiple characters in a window he called the “magic eye.” The typist chooses the correct character from the display.

Lin’s invention was not just the first typewriter for Chinese characters. Thomas Mullaney, a historian at Stanford University and author of The Chinese Typewriter: A History (2017), points out that it “combined ‘search’ and ‘writing’ for arguably the first time in history,” anticipating computer applications that have only grown more important with time. Unfortunately, Lin may have been too far ahead of his own time. Although he sold his design to the Mergenthaer Linotype Company, which filed a patent and made a single prototype, the typewriter was never manufactured.

Felix’s grandfather was a machinist for the Mergenthaler Linotype Company and acquired the sole prototype. Historians believed it was lost until it was discovered in his basement.

On May 2, Stanford University reported their acquisition of the typewriter. Regan Murphy-Kao, director of the university’s East Asia Library, “couldn’t be happier to have the opportunity to steward, preserve, and make this extraordinary prototype accessible for scholarship.”

You may also like: