My Funny Valentine: Sweet, Snarky, and Surprising Love Tokens from the Past

Long before Hallmark, lovers exchanged folded secrets, paper lace masterpieces, and wartime tokens—valentines rich in craft, emotion, and history.

In today’s modern society, most of us picture Valentine’s Day as a quick trip down the greeting-card aisle filled with pasteboard hearts, roses, a safe little verse, and perhaps a cherub or two. After all, that’s what commercialization has taught us to expect. Yet hidden just beneath the surface of this very commercial holiday is a world of handmade puzzles, lacy confections, vicious insults, mechanical marvels, and fragile love tokens carried through war.

These are the valentines that rarely get center stage, lost to history, yet sought after by collectors. These (mostly) love letters are among the richest in emotion and meaning. From 18th-century folded “puzzle purses” to World War sweetheart postcards, each one shows how people have expressed love, and sometimes annoyance, long before Hallmark conquered the commercial market.

Arranged roughly from oldest to most recent, this is a look at some of the most interesting, unusual, and frequently overlooked categories of Valentine collectibles.

Folded Secrets

Long before printed cards became common, lovers sometimes expressed themselves through intricate folded letters called puzzle purses. By the early 1700s, this cleverly folded form was being used in England and Colonial America to exchange romantic messages.

A puzzle purse starts as a simple square of paper. Through careful folding, it becomes a layered packet of triangles that must be unfolded in a particular order, often revealing numbered verses and/or small painted motifs, such as hearts or flowers, on each layer. The reading order literally led the recipient inward, toward a final declaration of love at the center.

Some of the earliest known puzzle-purse valentines date to the 1770s, with at least one surviving example dated 1769 in a Philadelphia collection. By the late 18th and early 19th centuries, sweethearts on both sides of the Atlantic were exchanging these handmade love confessions. These were intensely personal objects, often anonymous, sometimes signed, but always meant to be handled and reread.

Puzzle purses are scarce, which is part of their charm. Many do survive today in museum and archive collections, less so in private hands. When examples do appear on the market, especially early, heart-shaped, or elaborately decorated ones, they are treated as premium pieces of Valentine or manuscript ephemera. Condition is key: intact folds, legible ink, and vivid watercolor decoration can make the difference between curiosity and a bidding war.

The Birth of the “Modern” Valentine

By the mid-19th century, valentines had begun to look more familiar. In Britain and America, printers and stationers produced increasingly elaborate paper valentines featuring lace, embossed designs, and colored scraps.

In the United States, the queen of “The Card” was Esther Howland of Worcester, Massachusetts, who became known as the “Mother of the American Valentine.” After seeing imported English valentines in her father’s stationery store, she began experimenting with her own designs in the late 1840s, utilizing imported paper lace, floral cut-outs, and collaged verses. Her handmade cards sold so well that she built a small assembly line of local women who helped her layer her visions into three-dimensional cards.

Howland’s work, and that of her competitors, helped popularize the extravagant paper valentine, a lacy confection of pierced paper, colored backings, die-cut scraps, and sometimes tiny, applied beads, satin, or mirrors. Many museums hold vintage Valentine card collections featuring cards made with cameos, openwork and gilded lace, satin panels, and faux pearls.

In the 19th century, these cards would have seemed shockingly luxurious. Lace was a costly material in real life; paper lace, embossed to mimic its delicacy, suggested the same kind of care and expense. The message to the recipient was clear: you are worth the good stuff.

Paper lace cards range from modestly charming to “how-did-they-do-that” architectural masterpieces. Because many were saved in scrapbooks, good examples still surface in the marketplace. Look for deep layering of lace and colored paper, original verses still pasted inside, and strong maker connections such as Esther Howland or George C. Whitney. Prices vary quite a bit, with early or maker-attributed pieces generally commanding the highest prices.

Vinegar Valentines, the Sour Side of Love

Not every Valentine was sentimentally sweet. Beginning in the 1840s, a parallel tradition emerged in the form of vinegar valentines, comic cards meant to insult rather than woo.

These cards featured crude caricatures with rhymed verses aimed at “drunks, shrews, bachelors, old maids, dandies, flirts, and penny pinchers,” among many others. They were printed cheaply on single sheets of paper and sold for a penny. To add insult to injury (literally), recipients often had to pay the postage due upon delivery.

Publishers in the United States and Britain embraced the genre. By the mid-19th century, at least one major New York valentine publisher reported that sales of sweet and sour valentines were roughly equal. The popularity of vinegar valentines suggests that anonymous mockery was as much a part of the holiday as romance.

Imagine receiving a card and expecting a love token, only to discover you have been publicly roasted for gossiping, drinking, or being too stingy, complete with an illustrated verse spelling it out.

Many collectors prize vinegar valentines for their wicked humor. Many remain affordable, often selling for modest sums, though scarcer or earlier examples can bring more. These cards are frequently in rough condition because they were not meant to be cherished, and unlike a Howland card, they did not live life in a scrapbook. Bright lithography, legible verses, and particularly outrageous or taboo themes are especially sought after.

Moving Parts and Flirty Postcards

Image courtesy of Heritage Images/Getty Images.

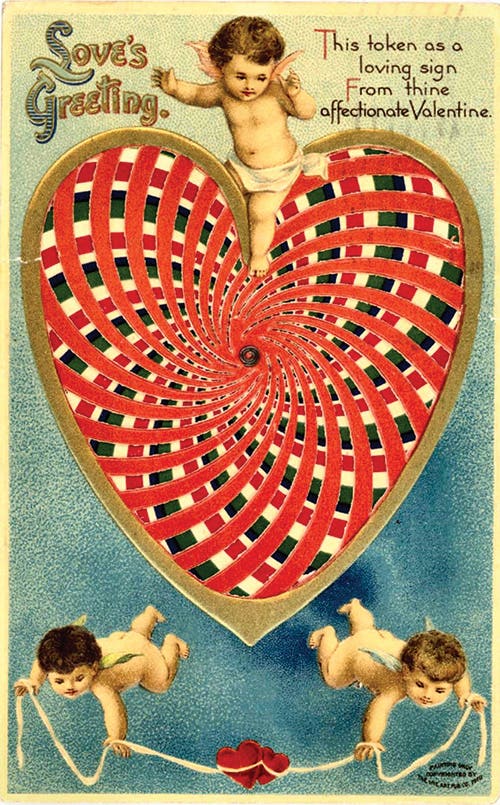

By the late 19th and early 20th centuries, new printing techniques and changing social norms brought playfulness and a hint of mischievousness to Valentine ephemera.

Mechanical valentines, with moving body parts, blinking eyes, or sliding panels, came into the market after die-cutting and chromolithography became widespread. Some were simple novelties, while others were surprisingly complex, with multiple moving parts activated by tabs, giving them a toy-like quality. Collectors should look for working mechanisms with intact parts.

Image courtesy of Heritage Art/Heritage

Images via Getty Images

After 1907, when divided-back postcards were approved in the United States, Valentine postcards exploded in popularity. Publishers produced designs that ranged from hearts and flowers to flirty couples and cheeky jokes about courtship.

Some of the most collectible postcards today are those that feel just a little daring. They feature suggestive imagery, suffragette themes, or humor that nearly strays beyond the social boundaries of the day. While many of these postcards remain inexpensive, scarcer artists or bolder themes can fetch higher prices. Look for crisp colors and interesting artists or publishers.

Image courtesy of Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group via Getty.

For original senders, postcards offered a safer way to flirt. A witty card with a double entendre could suggest interest while still maintaining plausible deniability.

Love from the Trenches

Nothing so powerfully emphasizes and focuses emotion as war, and Valentine-related sweetheart items from World War I and World War II are particularly poignant.

World War I Embroidered Silk Postcards

Image courtesy of Acabashi/WikiCommons.

Most World War I embroidered silk postcards were produced by women living in towns near the front lines in France and Belgium. Drawing on traditional needlework skills, they recognized a steady demand from soldiers eager to send something beautiful and meaningful back home.

Although each postcard was hand-stitched, production was surprisingly efficient. Women often embroidered repeated designs on long strips of silk mesh while working at home. These strips were then sent to urban workshops, including factories in Paris, where they were cut into individual panels and mounted onto postcard backs. Some were further enhanced with thoughtful details, such as small pockets for a folded embroidered silk handkerchief.

Silk postcards were not inexpensive. Wartime shortages of paper and ink drove prices higher, and when combined with the cost of silk and labor, a single card could sell for one to three francs, roughly a day’s wages for many enlisted men. Even so, their popularity never waned. Over the course of the war, an estimated ten million silk postcards were produced. For soldiers, these cards offered a way to send beauty home from devastation. For recipients, they were proof of love and survival.

Many embroidered silk postcards remain accessible to collectors today, with prices depending on condition, design complexity, and sentiment.

World War II Sweetheart Jewelry

Image courtesy of National Museum of American History/Smithsonian.

By World War II, the tradition of exchanging Valentine-related keepsakes had expanded into the practice of giving sweetheart jewelry. Lockets, brooches, and bracelets were commonly decorated with hearts, flags, eagles, or military branch insignia and were often designed to hold a photograph of a serviceman. Precious metals were tightly rationed for the war effort and reserved for weapons, vehicles, and aircraft, so most sweetheart jewelry from this era was made using non-precious or semi-precious materials. Bakelite, celluloid, wood, mother-of-pearl, shell, enamel, rhinestones, ivory, and simple wire constructions were widely used, reflecting both material shortages and wartime ingenuity.

More elaborate pieces do exist, though they are far less common. Some were produced in sterling silver, silverplate, brass, gold plate, or gold-filled metal, while a small number were made in platinum or solid gold. These items were not merely decorative accessories but daily, visible reminders of someone far from home. Today, pieces that retain original photographs, clear inscriptions, or identifiable branch insignia are especially desirable to collectors.

Messages Meant to Last

In this age of texts, e-cards, and mass production, early valentines feel startlingly intimate. A puzzle purse asks the recipient to slow down and unfold a message layer by layer. A paper lace creation signals care and expense. A vinegar valentine reveals the sharpest snarky edges of social life. A mechanical card offers surprises and often humor. A silk postcard from the trenches compresses longing into a few embroidered words.

These pieces tell stories. Whether those stories are sweet, playful, mean-spirited, or heartbreakingly sincere, none fit neatly into the modern tradition of a trip to the Hallmark store. That is precisely why collectors are drawn to them.

You may also like: