Dressing the Bombshells of Old Hollywood

From Marilyn Monroe to Elizabeth Taylor, Ceil Chapman’s understated elegance dressed Hollywood’s brightest stars—and today her timeless gowns are winning collectors’ attention.

Marilyn Monroe didn’t leave her wardrobe to chance. She understood how to stand out in the spotlight and dress for it. At one press event, she wore a silk cocktail dress that curved in all the right places. That wasn’t luck. That was Ceil Chapman (1912–1979).

There’s no shortage of male designers from the mid-20th century who’ve been canonized. Dior, Givenchy, Balenciaga—their stories have been immortalized. Ceil Chapman worked for many of the same clients during the same years and produced clothes that were arguably more wearable, yet most people today wouldn’t recognize her name.

But for two decades, she was the first call for many American starlets who needed to look luminous. Marilyn Monroe often wore Ceil Chapman. So did Elizabeth Taylor, Grace Kelly, and Debbie Reynolds. Some pieces were custom-made by the designer, while other dresses were bought off the rack by her customers from Saks Fifth Avenue or Neiman Marcus. Her gowns offered just enough glamour to turn heads but still felt right at home on the racks at Bergdorf’s.

And when cameras rolled, or flashbulbs popped, Chapman’s work held up. The fabric caught the light just right. The structure didn’t wilt. More than once, a gossip columnist would ask who made the dress. If the answer was Chapman, no one was surprised.

In this way, Chapman holds a different legacy: one built not on spectacle but on skill. Her dresses weren’t statements; they were solutions.

She never claimed to be a visionary nor opened a showroom in Paris. She focused on the work, and the dresses proved it. And today, collectors are finally beginning to catch up.

Early Beginnings

Born Cecilia Mitchell on Staten Island in 1912 and raised between Rosebank and Manhattan, Chapman began her career in 1940 with an early fashion business called Her Ladyship Gowns, formed with socialites Gloria Morgan Vanderbilt and Viscountess Thelma Furness. She then launched her Ceil Chapman label; Ceil, the nickname from her first name, and Chapman, her married surname. By the end of the 1940s, she was a quiet force in American fashion. She stayed out of the spotlight, but her dresses didn’t.

The Chapman Dress

The silhouette of Chapman’s dresses grabs attention both for its beauty and its technique. Chapman had an instinct for form and mastered the art of elegant draping. She used fine fabrics to create fluid folds and tightly gathered bodices that made the wearer feel elegant, beautiful, and contained. She let the seams and darts do the work rather than rely on frills or tricks.

Champman’s bodices are usually fitted, sometimes with internal boning. The skirts might flare or taper, but always move gracefully. Torsos are often gathered or wrapped, creating shape without bulk. Chapman had a way of making chiffon look sturdy and satin seem soft.

Color mattered, too: icy blues, ruby reds, and classic black. Her embellishments were minimal—maybe a touch of lace, a well-placed bow, or a gathering of fabric near the hip.

And somehow, it never looked overworked. Even at the height of the 1950s excess, Chapman’s dresses struck a balance between glamour and wearability. She didn’t dress women to fit a mold; she broke the mold to fit the woman.

Market Value and Collectability

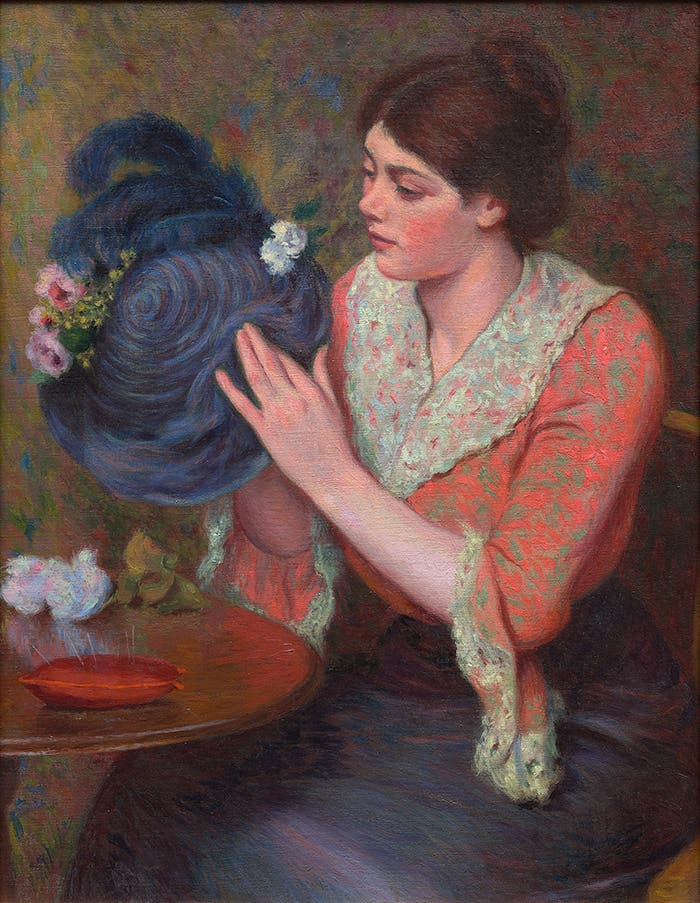

Costume Institute/Wikimedia Commons.

Today, Ceil Chapman is a sought-after name in vintage American fashion. Her pieces are not necessarily the priciest; they don’t bring anywhere near five figures like those of Dior or Chanel. But they are consistently purchased by collectors, stylists, and film costumers.

Dresses in good condition typically range from $300 to $1,500, depending on rarity, provenance, and size. Earlier pieces from the 1940s are scarcer, while those from the 1950s are more widely available but still command strong interest. Cocktail dresses outpace daywear in value, but Chapman suits and separates can also draw attention if well-maintained.

Like all vintage clothing, wear, price, and condition are inseparable. Look for intact boning, stable seams, and original zippers. Sweat staining and fabric pulls are common issues, particularly around the underarms and bodice. Labels are straightforward, usually with a white script on a black background—consistent across decades.

Resurfacing in Museums and Memory

Despite her prominence in her time, Chapman didn’t leave behind a strong biographical record. There were no tell-all interviews, and no design house to carry on her legacy. She died in 1979, largely forgotten.

However, in recent years, her work has begun to resurface, not just in vintage boutiques but also in museum collections and film wardrobes.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, and the Museum at FIT all hold Chapman pieces in their archives. Costume designers continue to draw inspiration from her when crafting mid-century looks for period films and television.

There’s no official archive and no active brand account. Even so, her dresses keep turning up in estate sales and vintage auctions. Sometimes, they’re misattributed. Often, they’re bought simply because they’re beautiful and wearable, even if the buyer doesn’t know the label yet.

A Return to the Rack

Vintage fashion is often dramatic, like wild prints and exaggerated silhouettes. Although Chapman’s work is much more subdued and may not stand out from the hanger amongst a swath of gowns, it is no less fashionable nor unworthy for purchase.

That’s why collectors seek her out, not just because of Monroe or Taylor but because the dresses themselves still work. They hold their shape, flatter the form, and politely embrace the wearer’s beauty.

And in a fashion market where so many names are forgotten within a season, that kind of staying power deserves a second look.

You may also like: